How Polarity Thinking Brings You the Best of Both Worlds

Adeline Leong is an undergraduate from NUS College who was interning with Studio Dojo over the summer holidays. In her time here, she grew interested in the practice of Polarity Thinking; in particular, how to identify and manage polarities in your day-to-day life. During a one-month field trip to Sulawesi, Indonesia, she took the chance to observe how local communities have organically responded to the polarity of Change and Preservation in their lives on the developing island. This post reflects her efforts to analyse local happenings using a Polarity Thinking lens.

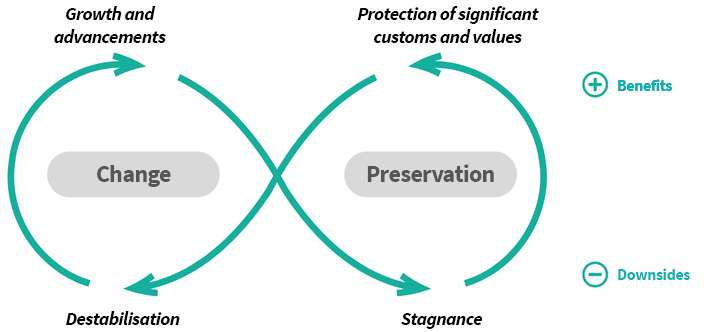

Polarity Thinking is a fascinating field that explores how opposing ideas (i.e. poles) can be interdependent and complementary.

To dispel tension between opposing ideas or values, we often assume that we must select one as the ‘best’. In doing so, we lose out on extracting value from its unchosen counterparts.

Polarity Thinking empowers the possibility of choosing all; through maximising the benefits of each while minimising any downsides. This is called Synergy.

Synergy

Entails embracing the tension between conflicting ideas:

Beyond a 50:50 compromise of preferences

Ideas work together for a greater purpose

Synergy

Entails embracing the tension between conflicting ideas:

Beyond a 50:50 compromise of preferences

Ideas work together for a greater purpose

Having a ‘Both/And’ framing is key.

For example, think of being ‘both Structured and Flexible’ instead of ‘either Structured or Flexible’.

To examine how this seemingly abstract practice of Polarity Thinking might manifest in reality, I spent a month in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, exploring how local communities navigate the polarity of Change and Preservation amid rapid state development of the island.

Some resisted the resulting changes to their longstanding ways of life, while others adapted or became resigned recipients.

In particular, two rural upland villages in the Maros District offer an interesting case comparison for synergy of the Change-Preservation polarity:

Both faced state-endorsed development plans in their area that overlooked local sociocultural contexts. Rammang-Rammang villagers’ expansive thinking enabled successful synergy of their desires for preservation with the state’s desire for development, but Barugae villagers’ capacity to synergise was hindered by an inflexible approach.

Want to learn more about Polarity Thinking before diving into this case comparison?

We recommend reading an Introduction to Polarity Thinking.

Unsuccessful Synergy: Barugae Village

Barugae was once a stronghold in candlenut cultivation. Unique sociocultural traditions emerged as a result. For example, their harvest tradition of Makkalice arose from an overabundance of candlenuts each harvest season.

Makkalice was a popular sociocultural activity with an important redistributive function: It opened Barugae’s expansive candlenut groves to any villagers to collect leftover candlenuts from previous harvests, regardless of grove ownership.

More vulnerable villagers, such as landless or land-poor families, women and the youth, viewed Makkalice as an important source of supplementary income.

It was a festive occasion. Villagers would joyfully convene over meals to discuss the best locations and set off in groups the next day. Children took this as an opportunity to play in the groves.

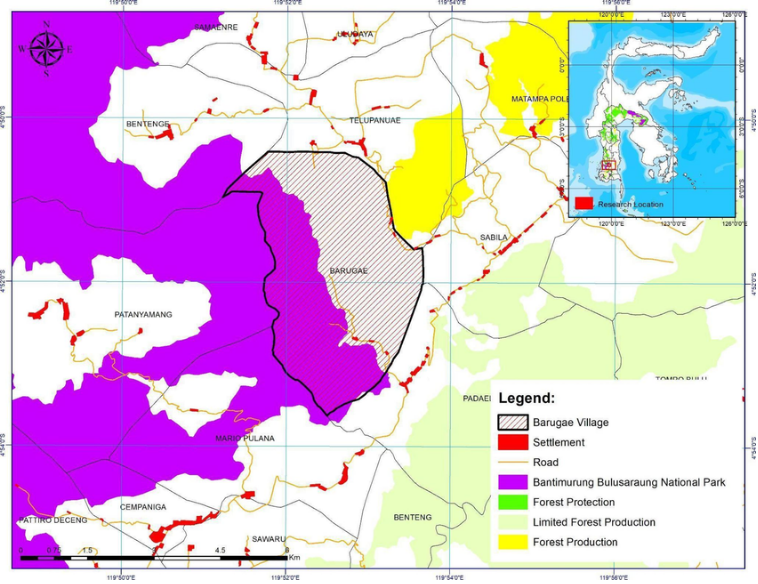

These vulnerable villagers were disproportionately affected when Makkalice faded with the decline in candlenut productivity, following the formation of the Bantimurung-Bulusaraung National Park (BBNP) in 2004.

Many of Barugae’s longstanding groves were incorporated into the park, becoming conservation enclosures that disallowed farmers from working the land. The resulting land squeeze drove farmers to repurpose their remaining land for more sedentary cash crops that provide less secure income flows.

Today, much of Barugae’s area falls within BBNP, and Makkalice is mostly a fond memory.

Figure 1: Location of Barugae Village and how it overlaps with Bantimurung-Bulusaraung National Park (Source)

Candlenut production is also tightly restricted; villagers shared that if a chainsaw is sounded in Barugae, the police will inspect the next day to ensure that no one has attempted candlenut cultivation in the conservation enclosures.

Applying a Polarity Lens

In endorsing the BBNP, the local government disrupted longstanding ways of life in Barugae. Villagers reminisce about their former stronghold in candlenut cultivation and related traditions.

Barugae villagers represent the Preservation pole, desiring the retention of their expansive groves to protect their livelihoods and customs. The local government represents the Change pole, desiring conservation development by enforcing land regulations through BBNP. Ironically, their conflicting desires are rooted in a shared fear of land dispossession.

Unfortunately, neither recognised that their poles addressed the same core fear, thereby missing the opportunity to align their desires for Barugae land usage. Instead, each saw their pole as the best way forward and made little effort to understand each other’s perspectives. The state did not properly consult locals before endorsing BBNP, and Barugae lacked strong self-organisation to defend their views. As such, the state’s conservation development plans overlooked the importance of Barugae’s groves in sustaining local livelihoods and traditions.

This led to an overemphasis on the Change pole, signalled by the destabilisation of Barugae’s income flows. Villagers, disadvantaged by their position in the formal power hierarchy, became resigned recipients of state-endorsed changes. Farmers resorted to alternative crops like corn and rice, despite these losing to candlenut in terms of price stability, production and net income-needs ratio. If a greater balance between Change and Preservation is achieved, the stability of Barugae’s income flows can improve.

Figure 2a & 2b: Cash crops, such as corn and rice, are now cultivated on the land where Barugae’s remaining candlenut groves once were.

Applying a Polarity Lens

In endorsing the BBNP, the local government disrupted longstanding ways of life in Barugae. Villagers reminisce about their former stronghold in candlenut cultivation and related traditions.

Barugae villagers represent the Preservation pole, desiring the retention of their expansive groves to protect their livelihoods and customs. The local government represents the Change pole, desiring conservation development by enforcing land regulations through BBNP. Ironically, their conflicting desires are rooted in a shared fear of land dispossession.

Unfortunately, neither recognised that their poles addressed the same core fear, thereby missing the opportunity to align their desires for Barugae land usage. Instead, each saw their pole as the best way forward and made little effort to understand each other’s perspectives. The state did not properly consult locals before endorsing BBNP, and Barugae lacked strong self-organisation to defend their views. As such, the state’s conservation development plans overlooked the importance of Barugae’s groves in sustaining local livelihoods and traditions.

This led to an overemphasis on the Change pole, signalled by the destabilisation of Barugae’s income flows. Villagers, disadvantaged by their position in the formal power hierarchy, became resigned recipients of state-endorsed changes. Farmers resorted to alternative crops like corn and rice, despite these losing to candlenut in terms of price stability, production and net income-needs ratio. If a greater balance between Change and Preservation is achieved, the stability of Barugae’s income flows can improve.

Figure 2a & 2b: Cash crops, such as corn and rice, are now cultivated on the land where Barugae’s remaining candlenut groves once were.

Successful Synergy: Rammang-Rammang Village

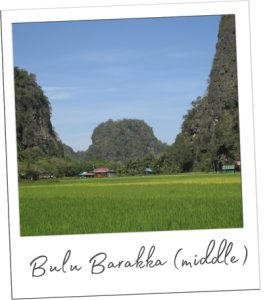

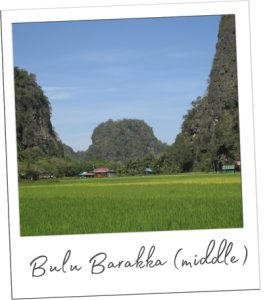

Rammang-Rammang lies within the world’s second-largest karst (i.e. limestone landscapes) area. These limestone formations are sacred to locals; they hide ancestral shrines, hold prehistoric evidence and provide natural water management.

The karst hill, Bulu Barakka, is of particularly high sanctity to Rammang-Rammang villagers. There is local lore that should Bulu Barakka be disturbed, all surrounding kampungs will be destroyed.

It was not surprising when the local government’s decision to permit marble mining at Bulu Barakka was met with strong local resistance in 2007.

But villagers would resist for almost a decade before succeeding in preserving their karst environments. The pivotal point came in 2013 when they turned to strategic ecotourism.

Figure 3 (right): Rammang-Rammang’s ecotourism initiatives have turned the village into a popular tourism attraction. (Source: Google)

Applying a Polarity Lens

Rammang-Rammang villagers’ desire to protect the sacred karst embodies the Preservation pole, while the local government’s prioritisation of economic development through karst mining demonstrates the Change pole.

Unlike Barugae, Rammang-Rammang villagers expansively considered this polarising dilemma. Instead of single-mindedly grappling for karst preservation or becoming resigned to state-enforced industrialisation, they recognised that both poles are motivated by a shared purpose to derive value from karst. Villagers imbue it with spiritual and cultural value, while the state seeks to excavate economic value. Their subsequent ecotourism strategy is ingenious in fulfilling this shared purpose: It protects the sacred karst as part of Rammang-Rammang’s ‘authentic’ tourism experience, in turn generating economic gains through tourism.

Further mining activity was discontinued, as ecotourism not only aligned with the state’s desire to grow Sulawesi’s tourism industry, but its economic success also aligned with the state’s core motive of economic development. In 2020, the state formally recognised ecotourism as an alternative economic driver to mining in the Rammang-Rammang karst area.

The villagers’ expansive thinking enabled synergy of the Change-Preservation polarity, leading to the mutually agreeable solution of ecotourism. Ecotourism capitalised on the benefits of both poles (e.g. income growth under Change pole; protection of culture under Preservation pole) and minimised their downsides (e.g. destruction of sacred spaces under Change pole; stagnant economy under Preservation pole). Their success was further empowered by effective local self-organisation, which amplified their efforts and voices.

Figure 4a (left): Boat tours to sightsee the karst mountain range are Rammang-Rammang’s key ecotourism initiative.

Figure 4b (right): Rammang-Rammang received the prestigious Kalpataru Award (circled) from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in recognition of their persistence in protecting the karst from the threat of industrialisation.

Applying a Polarity Lens

Rammang-Rammang villagers’ desire to protect the sacred karst embodies the Preservation pole, while the local government’s prioritisation of economic development through karst mining demonstrates the Change pole.

Unlike Barugae, Rammang-Rammang villagers expansively considered this polarising dilemma. Instead of single-mindedly grappling for karst preservation or becoming resigned to state-enforced industrialisation, they recognised that both poles are motivated by a shared purpose to derive value from karst. Villagers imbue it with spiritual and cultural value, while the state seeks to excavate economic value. Their subsequent ecotourism strategy is ingenious in fulfilling this shared purpose: It protects the sacred karst as part of Rammang-Rammang’s ‘authentic’ tourism experience, in turn generating economic gains through tourism.

Further mining activity was discontinued, as ecotourism not only aligned with the state’s desire to grow Sulawesi’s tourism industry, but its economic success also aligned with the state’s core motive of economic development. In 2020, the state formally recognised ecotourism as an alternative economic driver to mining in the Rammang-Rammang karst area.

The villagers’ expansive thinking enabled synergy of the Change-Preservation polarity, leading to the mutually agreeable solution of ecotourism. Ecotourism capitalised on the benefits of both poles (e.g. income growth under Change pole; protection of culture under Preservation pole) and minimised their downsides (e.g. destruction of sacred spaces under Change pole; stagnant economy under Preservation pole). Their success was further empowered by effective local self-organisation, which amplified their efforts and voices.

Figure 4a (left): Boat tours to sightsee the karst mountain range are Rammang-Rammang’s key ecotourism initiative.

Figure 4b (right): Rammang-Rammang received the prestigious Kalpataru Award (circled) from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in recognition of their persistence in protecting the karst from the threat of industrialisation.

Polarities are Dynamic

Nonetheless, Rammang-Rammang faces ongoing challenges: Recent state interventions threaten community-managed ecotourism initiatives, nearby cement companies pose risks to the Rammang-Rammang karst, and villagers’ livelihoods are now tied to unstable tourism flows.

Such instability in Rammang-Rammang’s outlook is reflective of the dynamic nature of polarities. Good polarity management goes beyond one-off synergy, requiring continual commitment to capitalising on the inherent tension between opposing poles. This tension is not static: The following diagram illustrates the ongoing flow of shifting emphasis from one pole to the other and back again.

If Rammang-Rammang does not sustain their present synergy of the Change-Preservation polarity (i.e. to maximise the benefits and minimise the downsides of each pole), they risk shifting into an over-focus on the Change pole given the evolving circumstances. This may result in destabilisation and undermine their past success.

Sustained Synergy Requires Commitment and Flexibility

Expansive thinking was key to Rammang-Rammang’s past success in synergising polarity. However, sustained synergy requires continual commitment and flexibility. Achieving the following is a strong starting point:

Understand the equivalent value of each pole, rather than shortlisting one as the optimal choice.

Recognise that the poles actually work towards achieving a greater shared purpose, and establish what this is. Conversely, consider the shared deeper fear that both poles aim to avoid.

Be open to alternative action steps or strategies for achieving the shared purpose among all key stakeholders.

Having effective dialogue between key stakeholders of diverse perspectives is helpful towards achieving this 3-pronged framework for sustained synergy. At the very least, further polarisation and unnecessary conflict is avoided.

In Conclusion…

It was inspiring to learn how local communities in Sulawesi, Indonesia, organically managed the Change-Preservation polarity in their day-to-day lives, even without formal knowledge of Polarity Thinking!

Indeed, some manage polarities well through instinct and circumstance. However, having an understanding of the Polarity Thinking concept can also structure your responses with greater intention.

Even just identifying your dilemma as a polarity may prompt you to impartially appreciate the value of each side and explore ways of aligning them towards a greater purpose.

The next time you are faced with a zero-sum choice, consider if this is really a choice that you have to make. It might just be possible to have it all!

All the best!

Adeline